When you get off the bus in Mayfield on Cork City’s northside, you pass two bookies and a Saint Vincent De Paul shop on the way to a warehouse owned by one of Ireland’s biggest moneylenders, where its tangled web of 18 companies with millions tied up in them is based.

For the last week, a surge of panicked parents have been landing into the SVP shop looking for uniforms, shoes and schoolbags, according to manager Ann Murphy.

Just up the hill, staff at Marlboro Retail Ltd are experiencing a surge in applications too, so much so that they are taking two weeks to process, as families struggle to cope with rising costs.

Many Cork people are familiar with the Murray family’s money-lending venture. It was first set up in 1952 on Patrick Street by the late Raymond Murray and has since become one of the country’s most successful licensed moneylenders, selling products on credit and issuing high-interest loans.

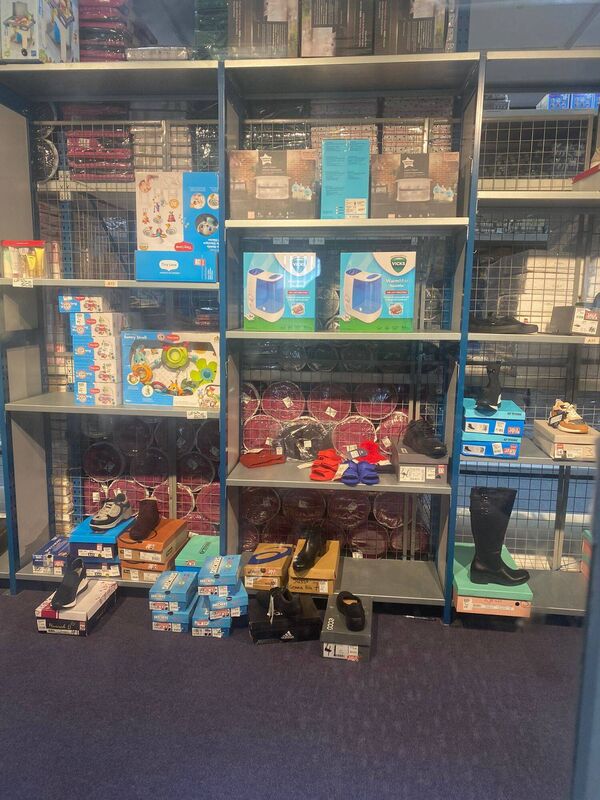

At the company’s northside warehouse, you can purchase a wide range of items from well-known brands, such as a baby walker, a pair of Nike runners, or even activewear from Laura Whitmore’s new collection with Dare 2B.

You can pay off your purchases over 21 weeks interest free, as one of 60 agents that the company employs nationwide visits your home weekly to collect payment.

But there is a catch — the prices of the products are hiked compared to what they normally retail for, so you end up paying more, for example €20 more for a digital thermometer than what you’d pay in Boots.

The entrance to the shop is relatively drab, but through the windows of two closed doors, aisles of products can be seen, well-lit and on display outside of their boxes — but I’m told that customers aren’t allowed to go in to browse.

The woman behind the counter takes my details and explains that to start with I can buy between €200 and €300 worth of products on credit, and if I pay the money back on time and build up my credit, I will be able to purchase a greater value of products, and it’s all interest-free.

What about loans? Those are not interest-free, and the staff-member can’t remember what the annual percentage rate (APR) is, but she tells me that after building up credit with them over time, I will then be able to take out a small loan, and that the agent will tell me the details when they call out.

In a nook around the corner the company’s moneylender’s license is pinned to the wall. It states that the starting APR is 72.51% for a loan paid with 21 weeks with a 14c collection fee per euro. The APR goes up the longer it takes you to pay, while the collection fee per euro borrowed reduces, to 10c per euro.

If you take out €100 and it takes you a year to pay it back, the loan will cost you €154 in total.

This business model has worked out well for the directors of Marlboro Trust (Finance) DAC, Raymond, Kevin and Cathryn Murray, and Brian and Philip O’Sullivan, who are also the directors of 15 of the other companies registered at the Mayfield Business Park.

Despite the setbacks of Covid, the retail end of the business turned over €19,633,956 in 2021, just under €2m more than it did in 2020. It had a retained profit of €980,624 at the end of the financial year.

The companies’ net assets also increased from €12,180,383 in 2020 to €12,851,007 in 2021.

The loans branch of the business is also making a profit and it had €5,426,189 in retained earnings at 31 August 2021.

With companies in security, investments and property, the Murray empire stretches beyond the operations they are best known for.

According to its latest accounts, its investment company Adam and Eve Limited had over €2.3m in retained earnings, and its property business Hillcrest Holdings had over €5.26m in net assets.

The Murrays are clearly proud of the network of businesses they have built. A sign on the way provides a timeline of the last 57 years.

Raymond Murray Senior started working life in the Murphy’s Brewery, where his father also worked. He came up with the idea to “enter into the home collected credit business selling bedclothes, clothing etc.”

Raymond became a multi-millionaire in his lifetime and moved to Spain. His business, which he eventually handed over to his children, grew far beyond what he ever could have expected when he left his brewery job, doing particularly well during the recession.

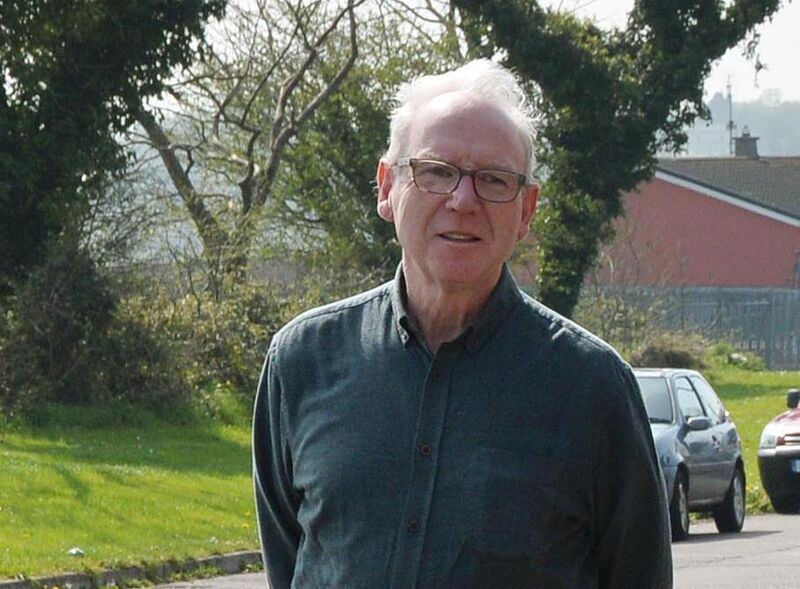

Mayfield local and Worker’s Party Cllr Ted Tynan has seen the impact pressure to pay back loans can have on vulnerable families.

Though Mr Tynan recognises that licensed moneylenders like Marlboro Ltd is operating legally, he says, moneylenders target people who have fallen on hard times.

Mr Tynan fears that people’s financial predicaments are only going to get worse as the cost-of-living crisis deepens.

“For the legitimate operators, there is a regulator, but people need to be well educated about what they are getting into.”

As for illegal moneylenders, or ‘loan sharks’ he has seen more than one family fall foul of them.

“I have met many people over the years, many of them women, who would have run up huge debts with moneylenders, and who would have been under pressure to draw down and hand over their children’s allowance before their kids saw any benefit from that money,” he says.

Socialist TD Mick Barry has questioned why moneylenders are allowed operate at all.

“It is disgusting that moneylenders licensed by the Central Bank have been permitted to charge an APR of up to 187% on loans rising to 288% once collection charges are included,” he said.

“The Government’s proposal to cut the maximum simple interest charged to 48% per annum does not go nearly far enough.

“Alongside a far more drastic cut and a garda clampdown on illegal money lending, demand needs to be cut by combatting poverty in this cost-of-living crisis,” he said.

On the bus back from Mayfield, I get chatting to a local woman headed for the city centre. She asks me what I’ve been doing there. I told her that I went to check out the Marlboro Trust Store, but that I didn’t buy anything.

“Oh no, you would be better going into town,” she tells me.

“People don’t go there unless they have to.”

Those who use moneylenders are at risk of a cycle of borrowing, increased indebtedness, and inability to pay, writes

Advocacy groups for the most financially vulnerable have raised concerns about the role of high-interest moneylenders during the cost-of-living crisis.

Hundreds of thousands of households in Ireland use moneylenders every year, with experts saying many people seek risky loans at times of huge financial burden, such as the back-to-school period and Christmas.

“For families, where other forms of credit are not an option, we do hear of them going to moneylenders,” said Stephen Moffat, national policy manager at Barnardos.

People who borrow from moneylenders come from all backgrounds, but research has shown the majority who turn to them are women with children.

A policy document from the Department of Finance says those with poor credit who use moneylenders are at risk of ending up in a “cycle of borrowing, increased indebtedness and have an inability to pay”.

A new cap on the interest rates moneylenders can charge was brought in under legislation passed this year, however, they can still legally charge rates of up to 128% on money borrowed.

The Society of St Vincent de Paul is urging the Government to progressively lower the maximum annual percentage rate (APR) to protect vulnerable households.

Dr Tricia Keilthy, head of social justice at SVP, said: “Within the act, importantly, they have provision for ministerial order to adjust the cap. That cap should be phased and lowered over a number of years.”

This should be done, according to Dr Keilthy, in a manner that does not have unintended consequences such as pushing more people to unlicensed moneylenders.

“The issue with moneylending loans is people tend not to tell us. They feel embarrassed. It might not come up in initial conversations but our volunteers do get to the bottom of it.

“The legal moneylenders are one route. With the illegal ones, they’re less likely to disclose it. There have been a few cases we’ve seen where people have taken a loan out from an illegal lender.

Junior Finance Minister Seán Fleming told the Seanad in June that a “balance has to be struck” in terms of the legislation.

“We want to make sure that the 30 companies that are here stay in business and can operate viably,” he said.

“If they disappear, everybody will go to loan sharks. We have to avoid that.”

The rather opaquely named Consumer Credit (Amendment) Bill was signed into law by President Michael D Higgins earlier this summer.

The Government said its main purpose was to restrict the total cost of credit on moneylending loans.

Licensed and legal moneylending in Ireland can take a number of forms.

It can take the form of cash given out as a loan, but can also involve the selling of goods on credit from a retailer or the purchase of goods from a catalogue.

Under the law, a moneylending agreement is when the total cost of credit is in excess of 23% APR — rates are usually far in excess of this.

In comparison, credit unions can charge a maximum APR rate of 12% but loans are often significantly lower than this. Banks would typically charge less than 10% on loans.

Under the new laws, the maximum rate of simple interest chargeable per week can only be set at 1% or less.

Simple interest for the year can be a maximum of 48%. However, that would equate to an APR of 128%.

The law also abolishes home collection charges, provides for online repayment books, and changes the licensing regime so licences are in place for five years rather than one year.

Currently, there are 32 moneylenders registered with the Central Bank.

Included on that list are companies such as Shop Direct Ireland, which trades as Littlewoods, and Oxendales, which has sites such as Simply Be and Jacamo.

At the end of 2020, there were 283,143 people using moneylenders in Ireland and they owed over €141m.

This worked out to an average of €498.75 per person.

Details published by the Central Bank include the indicative APR a customer would face, including a collection charge, with some rates as high as 210.7%.

Such high rates can turn short-term loans into ones that mean a high repayment very quickly.

“Although we estimate that it is likely to be anywhere up to 2.4 times this amount,” they said. “Thinking of community wealth depletion in this way is sobering”.

The biggest player in the Irish market — Provident Financial — exited last year and research from St Vincent de Paul suggested people who had borrowed from Provident would turn to family and friends for a loan, or to another licensed moneylender.

The survey results also suggested two major pinch points where people had turned to Provident for a loan — Christmas and back to school.

Ahead of new laws being introduced earlier this year, the Government sought the views of the various parties involved through a public consultation.

Credit unions and NGOs urged a cap on interest rates charged by moneylenders as it would offer protection to vulnerable consumers from low-income households who avail of the services of licensed moneylenders.

Some of the submissions pointed to how essential it was for low-income households to have access to short-term credit.

Six submissions from the moneylending sector argued against an interest rate cap. Among their arguments was that people in need of credit would turn to unlicensed moneylenders.

“The general consensus among licensed moneylenders was that the credit unions would not be able to meet consumers demand for short-term credit if a cap is introduced and licensed moneylenders would leave the market,” the Government’s regulatory analysis of the legislation said.

A further set of policy proposals developed by the Department of Finance delved into the importance of reform in the sector.

It said: “Recent research indicates that many customers of moneylenders are located all across the country, the majority are female, and have children.

“In addition, many borrowers are working, have a transactional banking relationship and there is a spread across all socio-economic groups.

There is also a danger that some customers end up in a cycle of borrowing, increased indebtedness and have an inability to pay.”

The department said research also suggested that staff of moneylenders are “also typically incentivised” to maximise earnings and may make decisions to lend based on profits, despite the potential risk to customers.

It said consideration must be given to any possible negative effects of reform, such as an increase in illegal moneylending.

It also recommended a lead-in time for some of the measures to take effect, such as the abolition of home collection charges.

When the legislation became law in June, the Government hailed it as an important step in protecting the most vulnerable.

Mr Fleming said: “Only by regulating these interest rates can the Government better protect people. I would urge anyone experiencing financial difficulty to please contact the Money Advice and Budgeting Service.”

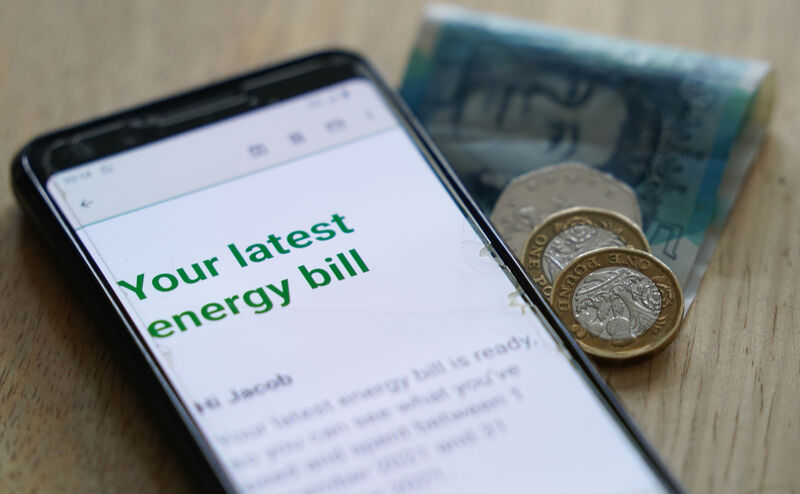

The scrutiny placed on money lenders from this new legislation comes as households around the country face significant pressure from the rising cost of living.

A report published last week by the Banking and Payments Federation showed a surge in people accessing credit from financial institutions in Ireland.

While personal loan drawdowns increased by 20.1% to €414m in the second quarter of this year, the value of loans that were listed as “other” and not car or home improvement loans increased by almost 60% to €146m.

A recent survey from the Irish League of Credit Unions also found more parents are getting themselves into debt over back-to-school costs, and one in 10 are considering using an illegal moneylender.

In its back-to-school survey for 2022, the parent of a secondary school student told Barnardos they had bought all their books for first year and was then told she needed an iPad.

“I had to borrow for that,” the parent said.

NGOs have urged people to explore alternatives before turning to a moneylender, even if they have bad credit.

This includes going to their credit union or micro-loans for social welfare recipients.

Social welfare supports such as an additional needs payment should also be sought if a household is in difficulty, they said.

Stephen Moffatt from Barnardos said a big concern this year for people is where they will access funds for such significant outlays as back-to-school costs.

“It’s people not having the same sources they could rely on in the past,” he said. “They might have been able to put some away for a time like this or turn to family members, and they can’t now.

“There are cases now where families are struggling. They are then falling into arrears for different bills. They’re saying ‘I’m cutting back as much as possible but things are only getting worse. How am I going to catch up here?’

Mr Moffatt said that for people in difficulty, the additional needs payment should have a quicker turnaround for families who urgently need it.

“Sometimes families could be waiting five or six days for the payment,” he added.

“They might not have five or six days.”